By Dana M. Grimes, Esq.

Yesteryear: The Era of “Pressing Charges”

Yesteryear: The Era of “Pressing Charges”

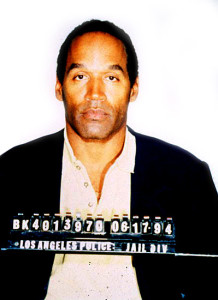

Even before O.J. Simpson murdered his wife, Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman in 1994, prosecutors in many jurisdictions, including San Diego, were developing a different approach to domestic violence cases. Domestic violence is defined as “abuse committed against . . . a spouse, former spouse, cohabitant, former cohabitant, or person with whom the suspect has had a child or is having or has had a dating or engagement relationship.” (Pen. Code § 13700(b).) Abuse is defined as “intentionally or recklessly causing or attempting to cause bodily injury, or placing another person in reasonable apprehension of imminent serious bodily injury to himself or herself, or another.” (Pen. Code § 13700(a).) Though the data is hard to compile, according to a comprehensive study conducted ten years ago, approximately 1.3 million women and 835,000 men are physically assaulted by an intimate partner annually in the United States. Patricia Tjaden & Nancy Thoennes, U.S. Dep’t of Just., NCJ 183781, Full Report of the Prevalence, Incidence, and Consequences of Intimate Partner Violence Against Women: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey, at iv (2000), available at http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/nij/pubs-sum/183781.htm.

Traditionally, the wife or girlfriend would call the police to report that her significant other had hit her. The police would respond to the call, but leave if the victim recanted at the scene. If she did not recant at the scene, the police would arrest the man. He would post bail (or, more accurately, the female victim would post the bail, out of limited family assets). Then the victim would decline prosecution, and the case would be dismissed by the prosecutor.

This practice led to the phrase “pressing charges,” as in, “If she doesn’t press charges, the case will be dropped.” This phraseology is still used today, despite the fact that it has very little relevance. A victim today has no ability to “press” or “drop” charges. If a prosecutor believes the victim’s first story, that he hit her, and not the later story recanting the abuse, the man will be charged regardless of the victim’s opinions, demands, wishes, new stories, etc. In some cases this approach has protected victims who would otherwise be unwilling or unable to protect themselves from the dangerous people they are involved with. In other cases, it has led to state interference and millions of taxpayer dollars wasted on highly dysfunctional and volatile – but not physically abusive – relationships.

Today: Someone is Going to Jail

Police policies, prosecution policies, and the law, have changed radically in the last 20 years. Today, if you see the San Diego Police Department responding to a domestic violence call at that house down the street, then tonight, you can bet money that one of your neighbors is going to be sleeping at central jail. In the majority of the cases with no injuries or minor injuries, the case will be issued as a misdemeanor (usually Pen. Code §§ 273.5 or 243(e), and sometimes with additional charges preventing the victim from calling 911).

Even in a low level, misdemeanor domestic violence case, police policy is to book on felony charges, so it will be harder for the defendant to post bail. This gives the victim and defendant some time to cool down, minimizing the change that the fight will escalate (and also minimizing the chance that the police will have to respond again – they hate DV calls). The current bail schedule in San Diego County is $15,000 for Penal Code § 273.5 and $10,000 for Penal Code § 243(e). Bail stacking often results in felony bails in the range of around $25,000. Posting of bail leads to problematic consequences, the brunt of which are often felt by the alleged victim. She will scramble for a babysitter, spend her entire night trying to track her partner down, and exhaust her savings scraping together the $2,500 or so it will cost to hire a bondsman to bail him out.

The bondsman is unlikely to volunteer this information to the victim, but in the less serious domestic violence cases, if she waits for her husband’s arraignment (which will occur within three court days of his arrest, not including weekends or holidays), he will be released OR (on his own recognizance – no bail needed). In other words, what she is buying for a few thousand dollars is often a day or two less in custody. In bigger cases, with say $100,000 bail, the $10,000 that would go to the bondsman can be used to hire an attorney to argue for an OR release, and to defend the entire case. If the defendant is likely going to end up having to go back to jail because of some reason like his record or her injuries, he might as well save his custody credits on the front end by not posting bail, thereby saving his family the money.

Thus, in the typical misdemeanor case, the defendant is booked on felony charges, the victim posts bail on the felonies, and the defendant is released. Some of these charges are not issued. If the case is issued as a misdemeanor, he later receives a notify letter from the office of the prosecutor that he is being charged with domestic violence. Now, if the victim recants by calling the police or prosecutor, and says she made it all up, that is not by any means the end of the case. A prosecutor in a specialized unit will review the police reports and the 9-1-1 tape. (The 9-1-1 call of a terrified Nicole Brown Simpson placed in October of 1993, as OJ was kicking down her door, can be heard on YouTube.) The prosecutor and/or DV detective will conduct follow-up interviews of the victim and any other witnesses, and the victim will be referred to domestic abuse support services. If the victim and her children need a domestic violence shelter, they are provided information on shelters such as Becky’s House, sponsored by the YWCA of San Diego. (Usually a condition of release on bail in a domestic violence case is a no contact order between the defendant and alleged victim.)

If the Domestic Violence Case is Issued by the Prosecutor’s Office

If the victim has some minimal bruising, and the defendant pled guilty to one of the two commonly used misdemeanor domestic violence battery sections, Penal Code §§ 273.5 or 243(e), the conditions of probation will likely include five days of picking up trash or volunteer work, a fine of around $700, a protective order or stay away order as to the victim, and a very intense 52-week DVRP program.

If the case goes to trial, the rules of evidence have changed. Two years after the murder of Nicole Simpson and Ron Goldman, former Houston Oilers and Minnesota Vikings quarterback Warren Moon was charged with hitting and choking his wife Felicia (their 7-year-old son called the police). At trial, Felicia testified that the scratches and bruises on her neck were inflicted when Moon was defending himself from her attack, and Moon was acquitted. The prosecutor was not allowed to introduce into evidence several prior incidents in which Moon had allegedly attacked Felicia.

Now, at least in California, prior acts of domestic violence that have occurred within the past 10 years are presumed admissible under Evidence Code § 1109, and can be persuasive to jurors. (The 9-1-1 calls will come into evidence as spontaneous declarations under Evidence Code § 1240.)

In Crawford v. Washington (2004) 541 U.S. 36, Justice Scalia (of all people) wrote the majority opinion that the Sixth Amendment confrontation clause prohibits the introduction into evidence of testimonial hearsay statements of a witness who the prosecution cannot locate. However, most recanting victims show up in court in response to the prosecutor’s subpoena, and they show up with a new story. After she testifies that she got the black eye by walking into the door, the prosecutor calls the patrol officer who responded to the call to the stand, and he testifies that she told him the drunken defendant slapped her, threatened her, and yanked the phone out of the wall when she tried to call her mom.

That is not to say that all domestic violence cases are a slam-dunk for the prosecution. On the contrary, recanting and non-recanting victims of domestic violence alike often have baggage as witnesses and sometimes a history of being the abuser as well as the abused party. There is more of a revolving door between victims and defendants in domestic violence cases than perhaps in any other area of criminal law. Therefore, these cases can be challenging to prosecute, even after the aforementioned dramatic public policy changes and changes to the laws of evidence.

The Emotional Nature of a Domestic Violence Case

Domestic violence cases are, as a general rule, a nightmare to defend. That is because regardless of the guilt or innocence of the defendant, one thing is almost always true: the case is born out of a tangled mess of a dysfunctional relationship that he or she has a complete lack of objectivity on. We often refer domestic violence cases to colleagues, simply because the cyclical nature of domestic abuse, the revolving door of defendants and victims, and their often co-defendant dysfunctional way of relating to each other, make these cases exhausting to deal with. Many criminal laws proscribe conduct that is based on impulsiveness and/or poor decision making. Domestic violence laws are unique in how personal they are – they are regulations on romantic relationships. They essentially outlaw the psychologically unhealthy manner that two people have defined as their way of relating to each other.

The felony or misdemeanor DV cases that we accept are usually out of the ordinary. In one particularly serious case, our client stabbed his partner with a knife (he survived; they got back together). In another case, our client was the 100-pound wife of an NFL player. We cannot disclose his exact weight; let’s just say it was well over twice as much as hers. He told law enforcement his wife had scratched him on the forearm (he had played a game that day, so it is hard to say where those particular scratches came from). One of the officers who took her to jail asked the football player/victim for his autograph.

Women remain more likely to suffer physical abuse than men. However, men historically have been more likely to endure physical abuse in silence; in addition to the shame women endure in reporting it, they must overcome gender stereotypes. Often bigger and stronger than the abusive partner, they are embarrassed by the power dynamic leading to the abuse and do not defend themselves nor report the problem. This leads to what experts believe is a grave under-reporting of instances of abused men. As noted above, when the police are called on a DV case, someone is going to jail. Usually that someone is the man. Thankfully, the prosecutors who evaluate these cases for possible prosecution take a much closer look at the facts than the law enforcement agency that responds to the scene. Unfortunately, an arrest for DV can be damaging to a person’s reputation and child custody goals, even if it does not result in a criminal case.

Lessons from the OJ Simpson Murder Trial

It is hard to make generalizations about criminal law from the OJ Simpson case, because it was such an anomaly in so many ways. The only typical thing about the OJ Simpson case was that the relationship between OJ and Nicole was – before he killed her – a very standard domestic violence situation. The problem with prosecuting domestic violence cases, and defending domestic violence cases, is that usually the criminal conduct is a lifestyle that no one – except the court system – wants to change. There is no way for the prosecutor, the defense attorney, or the judge, to know which one of a thousand couples in which one partner or both slap the other around, is going to escalate to the point that somebody gets killed.

One of the policy considerations behind the prosecution of these cases is that no law enforcement agency wants to be the agency that was not tough on a misdemeanor defendant who ends up murdering his ex, like OJ did.

To be fair, there are deeper policy considerations than the “not on my watch” policy: the defendant who slaps his girlfriend around (or the alleged victim who falsely accuses him of it to get leverage in the custody battle), learned that behavior from generations of dysfunctional family relationships, and if the state does not intervene to stop the cycle, it is likely that it will not end. Battered intimate partners, of course, are not the only victims of abuse – in 2002, it was estimated that anywhere between 3.3 million and 10 million children witness domestic violence annually. Research demonstrates that exposure to violence alone can have serious negative effects on children’s development, even when the children themselves are not victims of violence. Sharmila Lawrence, National Center for Children in Poverty, Domestic Violence and Welfare Policy: Research Findings That Can Inform Policies on Marriage and Child Well-Being 5 (2002). The problem is, state intervention is fraught with human error, and dysfunctional relationships involve the most complex of human emotions. Sorting through the stories of a victim and defendant in an attempt to find the truth is a difficult but important task for the criminal justice system.

An overwhelming number of domestic violence cases involve low income families and individuals receiving public assistance, and studies consistently show a striking correlation between domestic violence and low income. (In a study of two California counties [Kern and Stanislaus], public benefits recipients had lifetime domestic abuse rates of 80% and 83%, respectively. Joan Meisel, Daniel Chandler & Beth Menees Rienzi, Domestic Violence Prevalence and Effects on Employment in Two California TANF Populations, Violence Against Women 1191 (2003).) Collateral consequences to these low income victims of domestic abuse (usually women, who has primary care of the children), such as payment of bail and court fines, loss of employment of the primary breadwinner and sometimes deportation of her husband, can be extremely detrimental to the abused victim. As a society, we need to be careful when crafting the punishment to fit the crime, that our punitive goals are tempered by a mindfulness of the collateral consequences to be abused intimate partner, and to their children.

In October of 2017, O.J. Simpson was released from prison, on parole, in Nevada. He had been sentenced to 9 to 33 years for a robbery involving sports memorabilia. He served 9 years, and was released immediately after becoming eligible for parole.